Alexander Muraviev gave an interview to Austria Presse Agentur. Belsat TV channel and the BIC journalists were involved in its preparation. This investigation was carried out with the support of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and CyberPartisans.

"Today I consider what happened to me a crime against justice. And all that happened was a crime," says Alexander Muraviev. When talking to journalists, he keeps confident, sometimes smiling and chuckling. Though he breaks down a couple of times — the businessman does not seem to like the questions about who was behind him, nor does he like the reference to his career as a failure.

To record the interview, journalists had to fly to the United Arab Emirates. This is where the businessman lives after he was released from the Belarusian prison in December 2022. His success story in Belarus wound up in court following a failed investment in the Motovelo plant. It started in the 2000s with the purchase of the Yelizovo Glassworks. The rise of this enterprise made Alexander Muraviev one of the most influential and media-rich Belarusian businessmen. BIC took a closer look at the personalities who stood behind him at that time and could help him build an empire.

The Motovelo Case

Alexander Muraviev and other defendants in the Motovelo case were detained in June 2015: Back at the time, he was trying to get on the flight from Minsk to Vienna. About a year and a half later, the court announced the sentence — 11 years in prison with asset forfeiture. The businessman was found guilty of fraud, theft, and tax evasion.

"I told him this: If you don't do it, you'll go to jail <...> I was not in favour of him going to prison. But I reminded him: ... if you are found to have violated the law and committed fraud, I will not be defending you. And he got jailed," this is what Aleksandr Lukashenko said about Muraviev after the sentence.

With these words, he put pressure on the court, the businessman insists in his conversation with journalists. The president’s statement came on the fourth day after the verdict was announced, when the decision had not yet entered into force, and the defence filed an appeal.

Muraviev served seven and a half years. Upon his release, in his conversation with journalists, he states that he wants to resume his business and gain access to assets. By the time of his release, Muraviev's Belarusian enterprises had gone bankrupt, and his companies in Austria had been liquidated. It was from there that he entered Belarusian business years ago as a director and co-owner of the ATEC Group of companies.

"They didn’t go bankrupt, they were robbed. These are different things," the businessman insists.

Someone took advantage of framing him, finding some pre-planned intent and imprisoning a person for 10 years, says Mikhail Kirilyuk, a lawyer at the National Anti-Crisis Management. According to him, the punishment imposed on Muraviev is disproportionate to the violation. What is described in the sentence as criminal actions is not considered a crime in the West, and such situations are considered as part of civil legal disputes.

"If you follow the description in the sentence, then there is no certainty that a crime actually took place <...> Did I buy the company or not? <...> Am I reserved the right to dispose or not? That is, if I considered it necessary that, to maximize profits, I need to pave the site and repay debts to the executive committee, including repaying debts to my own enterprise, then what's the problem?”

The rise of the "Glass King"

Back in the early 2000s, the glass business was on its rise. Since the 1990s, food industry enterprises in post-Soviet countries have suffered from a shortage of glass containers. The demand continued to exceed supply by the beginning of the 2000s. In Russia, for instance, instead of the required 8 billion beer bottles, only about 3 billion were produced. The glass container market in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine was unified, recalls Alexander Muraviev: "There were no obstacles to the movement of goods."

Simultaneously, the businessman claims ignorance regarding the industry's growth during that period:

"When ATEC bought shares, I did too as an executive, I wasn’t aware of market conditions at all, because at that time I had not sold a single three-litre jar. <...> The products that the Yelizovo Glassworks produced were not needed on the market at all. <...> There was a huge amount of challenges ahead to create new capacities and introduce them into the market," states Muraviev. And, in his words, Yelizovo did not produce in-demand, scarce glass containers.

Until 2001, seven glass-container plants operated in Belarus, recalls Muraviev. By 2002, three of them — located in the villages of Hlusha, Huta and Zalessie — ceased production. The four remaining ones — the Homel and Hrodna Glass Factories, Belevrotara and the Yelizovo Glassworks (based at Steklozavod Oktyabr) — had roughly equal capacities. At the same time, as noted by the businessman, in terms of technological equipment, Belevrotara, for example, was way ahead of Yelizovo.

In 2001, Alexander Muraviev became the owner and CEO of the Austrian company ATEC Handelsgesellschaft GmbH. [*] [*] [*] [*]

In 2004, he headed ATEC Holding GmbH. [*] [*]

At that time, the ATEC Group entered the Belarusian glass market: in 2002 it bought a controlling stake in the city-forming glass plant in Yelizovo from the previous foreign investor, the Canadian company Consumers Packaging Inc (CPI). In the mid-2000s it acquired Belevrotara, and in 2008 it launched glass container production at the Homel Glass Factory.

That is, the ATEC Group owned three out of four Belarusian glassware manufacturers. Yet there could be no talk of a monopoly position on the market, Muraviev insists. According to him, the market was common to several countries and competitors were aplenty.

However, having no previous connection to the glass industry, the businessman acquired several companies in a growing and potentially highly lucrative market. Influential partners could help him with that. Some of them were welcome in the highest offices.

An Insider in the Presidential Administration

For example, the businessman’s brother Sergei. He became a co-owner of ATEC Handelsgesellschaft in 2001 with a 10% stake. [*] [*]

At least in 2003 — early 2004, Sergei Muraviev combined his engagement in his brother’s business with work in the Belaya Rus company, owned by the Presidential Administration. [*] [*] [*]

It wasn't even individual companies that were being brought to heel by the managers, but entire sectors of the economy.

"Indeed, Sergei worked at Belaya Rus for two or three years. <...> I had no trade or investment relationships with this company. And the fact that my brother worked there — he gained extensive experience as a manager, as a specialist <...> Well, he wanted to work at Belaya Rus, and so he did, as some kind of manager. He implemented trade projects. My brother is an independent man," says Muraviev in his reply to a question from journalists about possible family patronage.

The companies owned by the ATEC Group developed rapidly in those years. For example, before its acquisition by ATEC, Yelizovo produced four types of glass jars and bottles, after which the plant's range expanded to more than 30 items. The company invested about $41 million in the plant renovation and production upgrade. From being an outsider, the company became one of the leaders of the Belarusian glass industry. From 2002 to 2006, the plant increased its production output by 6.5 times.

Another ATEC glass asset — the glassware production at the Homel Glass Factory — is also an example of this success. The ATEC Group began its design at the end of 2006. Two years later, production was put into operation. In 2011, yearly product output increased by approximately 30%, profits reached 15 billion Belarusian rubles (about $3.2 million), and profitability was almost 18%. There was enough money for both production and payments to suppliers. The average salary at the plant in 2011 increased from 1.7 million rubles to 3.3 million rubles (from $368 to $714).

Aleksandr Lukashenko himself noted the success of Yelizovo. In 2006, he said that the ATEC Group had "fulfilled all investment and social obligations" and cited Yelizovo as an example of how public and private capital should work. An additional sign of recognition for Muraviev was a medal for labour merit. Lukashenko nominated the businessman for the award in 2006.

"I was normal, I was ordinary, I was what I should be. <...> I simply did the work that a businessman is supposed to do. It's nothing special," assures Alexander Muraviev almost twenty years later.

The Motovelo Purchase

"He revived the village — it’s nice to live there. What kind of Austrian is he? He's our man. If this man can boost the motorcycle plant, then what are we waiting for?" — Lukashenko said about Muraviev in 2007. He was referring to the Motovelo plant, which the ATEC Group would acquire in 2007, pledging to invest $20 million in it to get it out of the protracted crisis.

The holding of "ordinary businessman" Muraviev ATEC bought Motovelo, beating the Italian motorcycle manufacturer Cagiva and the Amkodor company of businessman Alexander Shackutin (Aliaksandr Shakutsin). Cagiva was renowned worldwide as a competitor and winner in the prestigious road-circuit motorcycle racing event MotoGP. Shakutin was later referred to as Lukashenko's 'moneybag' and was sanctioned by the EU for this. The reason why the deal was not concluded with Shackutin remains unknown, and the sale to the Cagiva group was blocked by the authorities a few years earlier. Allegedly, the Italians would reduce the number of plant workers by two-thirds, the products would become too expensive for the consumer, and the Italian owner would eventually abandon the bicycle production. According to Muraviev, there were two more bidders for the purchase of the plant.

For some reason, Austrian investors from a secondary sector (at that time, ATEC was engaged in glassware production) attracted official Minsk more than the experienced Italian manufacturer and Amkodor, which was much closer in profile. Motovelo was sold without a tender to an Austrian company led by Alexander Muraviev for almost $7.3 million (15.6 billion Belarusian rubles).

The Austrian investor undertook not only to repay the company’s debts, which, according to our calculations, exceeded 35 billion Belarusian rubles ($16.3 million) but also to invest another $20 million in it. In addition, in 2012, ATEC pledged to increase production to 500 thousand bicycles and 30 thousand motorcycles.

This was an ambitious plan: in 2005, Motovelo nearly went bankrupt. Employees who were not paid wages went on strike and blocked Partyzanski Avenue in the capital. A year later, the equipment wear reached 95%. In 2006-2007, by decree of Lukashenko, the Minsk City Executive Committee attempted to save the plant and allocated a subsidy of 17.3 billion Belarusian rubles to the company (this is the amount before the 2016 denomination, i.e. more than $8 million). But there was a condition: in 2006, the plant had to increase production by at least 157.8%, and in 2007-2012, Motovelo had to produce 110% more items every year compared to the previous one. The support measures also involved a loan from the public purse in the amount of 18.3 billion Belarusian rubles ($8.5 million) and a loan of 3 billion Belarusian rubles ($1.4 million) from Belpromstroybank.

Since 2008 — a year after the purchase of ATEC — the company has been shut down several times. It was not possible to reach the planned indicators even in 2013. Then Lukashenko paid a visit to the plant, where they confirmed to him that the investor had indeed invested the agreed amount. However, only a small portion of it was allocated for the production development. Muraviev promised to see to it that all the plans come to fruition in the coming years and asked for instalment payments on loans. Lukashenko agreed to "lend a hand one last time", but promised to closely follow the dynamics of Muraviev's company.

At the same time, in September 2013, it was reported that other ATEC Group companies — the Yelizovo Glassworks and Homel Glass Factory — also had a hard time. The companies experienced financial difficulties, including being unable to repay loans. A month later, the authorities put their share in Yelizovo up for auction. To be fair, we should note that the shares of the glass plant were not the only asset that the government then decided to get rid of. Apart from these, shares of several dozen other companies were put up for auction.

Marks on Glass

It seems luck has ceased to favour Alexander Muraviev. Perhaps relationships with partners have gone wrong. In his conversation with BIC, the businessman insists that he did not depend on them.

"The judge tried to assert that everyone has someone above them, and the one who is above them has someone else above them. Yes, it wasn't my case. I am a manager, the way a manager of an ATEC enterprise group should be, who can at least assess the situation, make plans, and strive to see them fulfilled," says the businessman.

BIC, however, managed to find people who could be behind Muraviev.

Investments in glass companies in Belarus came through the Austrian company ATEC Holding. At different times it had several shareholders: the Austrian ATEC Handelsgesellschaft GmbH, the British J&W Sanderson Limited, as well as the Cypriot Permanent Trading Limited, Remolino Trading Limited and Gaflotrade Limited. The last sole owner of ATEC Holding in 2015 was Madison Park, S.A., which replaced Permanent Trading. [*] [*] [*] [*]

ATEC Handelsgesellschaft GmbH was established in 2001 by Austrian citizen Dr. Siegfried Kemedinger, who still extends various services to legal entities. [*] [*] Less than a month following the opening, Kemedinger transferred the company to Alexander Muraviev. He becomes the sole owner but later shares his assets with others. [*] [*]

One of its first shareholders with a 3% share became a citizen of Belarus Yauheni Chanau. This took place on the same day as Alexander Muraviev’s brother Sergei became a shareholder. At that time, he was one of the company directors. [*] [*] [*] [*] His name has already flashed in investigations on the underground empire of Viktor Sheiman, a man who is called the closest associate of Aleksandr Lukashenko and is accused of murdering his political opponents in the 90s.

Yauheni Chanau was born in Russia but served in the 5th Special Forces Brigade, located in Maryina Horka in the Minsk Region. From the end of 2019 into 2020, Chanau headed Guardservice, the first and so far only private security company in Belarus with the right to bear arms. [*] [*]

We talked about the connection between Guardservice and Sheiman in one of our previous investigations. Chanau was in charge of security at Belgeopoisk, a company with a state share. The company was later taken over by Sheiman’s people and explored gold deposits for them in Africa.

Alexander Muraviev strongly denies any ties with Viktor Sheiman.

"This is the first time I've heard that he [Yauheni Chanau] is Sheiman’s man. Back then [during his cooperation with Alexander Muraviev], he certainly did not have any contacts with Sheiman. At least I knew nothing about it," said the businessman.

In Muraviev’s words, Chanau was in charge of his security and made sure that the plant employees would not drink or steal. Chanau had a share in the business, but it was merely a token one.

"Chanau was one of the directors. <...> Chanau had rather narrow functions and these were outside of business. <...> He was in charge of the security service, including at the Yelizovo Glassworks. This was his core activity. He hired people, supervised them, appointed them so that they, in general, would make sure that they would not steal and, by the way, that drunk people would not go to work — that was his job too," says Muraviev.

Chanau was listed among the directors of ATEC Handelsgesellschaft until 2003, and among the co-owners until May 2004. [*] [*] [*] [*]

He was the director of one of the Belarusian ATEC companies Viklif/Elipak as early as in 2004. [*] [*] These are two names that the packaging company had at different times. In addition, while working for Muraviev, Chanau headed the ASA Special Forces Veterans Foundation. [*] [*]

The foundation and the representative office premises of ATEC Handelsgesellschaft were located on the same floor in a building on Niakrasava Street in Minsk. [*] [*]

Chanau went to work for Viktor Sheiman many years after completing his collaboration with Alexander Muraviev. And he wasn't alone. We studied the biographies of people who collaborated with Muraviev and counted about ten such examples. Several high-ranking employees of his enterprises subsequently became known as "Viktor Sheiman's people" and went to work in structures associated with the right hand of Aleksandr Lukashenko.

From Muraviev to Sheiman

Former CEO of Motovelo Siarhei Anoshka has worked with Muraviev in different companies since 1999. [*] He later became an employee of Avangard Gruzotrans. [*]

The contact of Avangard Gruzotrans in the state register is the email of Globalcustom, a company founded by Viktor Sheiman’s common-law wife Hanna Pushkarova, together with a relative of his previous wife. [*] The owner of Avangard Gruzotrans and the brother of Siarhei Anoshka’s wife Tatyana, Yury Hryshuk, also worked at Globalcustom. [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] Prior to that, he worked for Alexander Muraviev as the CEO at Viklif/Elipak. [*] Tatyana Anoshka also worked at the Viklif company. [*] From 2019 to 2020, she headed Globalcustom associated with Sheiman, and now she leads GBK-Shelkovyi Put, whose phone number is the same as Globalcustom's. [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] Yury Zhouner, who in 2004-2005 held a position in the representative office of ATEC Handelsgesellschaft in Belarus, is also linked to it. [*]

Thanks to CyberPartisans, we know that in 2010-2013, after being fired from Motovelo, Siarhei Anoshka, together with Viktor Sheiman, flew to Africa, the United Arab Emirates and Latin America at least four times. [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] Anoshka returned from one trip on a charter flight with Aleksandr Lukashenko’s "moneybag", businessman Alexander Shackutin (Aliaksandr Shakutsin). [*] That business trip coincides with the dates of Lukashenko’s visit to Latin America. [*]

Yauhen Zhouner worked as Siarhei Anoshka’s deputy chief executive of Motovelo under Muraviev. [*] In 2020, he was mentioned as a co-owner of Globalcustom and a specialist at Avangard Invest. [*] [*] He also headed the company Zim GoldFields Limited, which, through an offshore in Seychelles, as of 2018, was 70% owned by Sheiman’s son Sergei and mined gold in Africa. Thanks to CyberPartisans, we learned that Yauhen Zhouner and Sergei Sheiman have a long history of relations. Back in 2009-2012, they repeatedly traveled abroad together by car. Siarhei Anoshka joined them on a few occasions.

Alexander Muraviev himself also has a flight history with Sergei Sheiman. On February 21, 2012, they shared a flight to Abu Dhabi. [*] [*] They were on the same flight again on March 1, 2012, returning from the Emirates to Belarus. Prime Minister of Belarus Mikhail Myasnikovich also took the same plane. [*] [*] [*]

The businessman puts both situations down to coincidence: "I did see Myasnikovich several times on the plane. I still don't know who Sergei Sheiman is. ... I took the flight that was convenient for me. It was not like we were sharing the flight intentionally. I don't give a damn who is on the same flight with me".

On October 25, 2011, Alexander Muraviev was returning to Minsk from Vienna on the same flight with his business partner Alexander Tudvasev. [*] [*] On the same flight to Minsk were the wife of Aleksandr Lukashenko’s middle son, Dmitry, Anna, and businessman Alexander Zaytsev, who was close to Lukashenko's other son, Viktor. [*] [*]

In 2011-2013, the Motovelo branch employed Aliaksandr Nikalaichanka. [*] Following the Motovelo criminal case, in 2017, he headed the Polessky Yantar company, owned by Globalcustom-Management. [*] [*] [*]

Muraviev denies these people were his ties to the authorities: "If these ‘ties’ somehow represented my interest or connection, I probably would have enjoyed better conditions in prison. These ‘connections’ never manifested themselves in any way."

During the investigation, Siarhei Anoshka was one of the suspects, but later became a witness. According to Muraviev, Anoshka was "posing" during the trial, and his interrogation reports are "the most fun, both before the trial and in court."

From the verdict, the BIC learned that Anoshka, for example, repeatedly asked Muraviev, as the "major shareholder," why Motovelo was not being reconstructed. "By the fall of 2008, it became clear that Motovelo was an unprofitable company. The plant required upgrade and renovation... During the first year of his [Siarhei Anoshka’s] tenure, no global large-scale modernization and renovation was done," Siarhei Anoshka’s testimony is quoted in court documents. [*]

"I told him right in the courtroom [...]: ‘Anoshka, why didn't you buy the machines? You're the one in charge, why didn't you buy them?’ He says: ‘There were obligations to return the money received at a specified time.’ ‘And why didn't you buy the machines when you received the money, you creep?’ He says: ‘Because when I was extended a loan from ATEC Holding, I paid salaries, I paid off tax debts,’” recalls Muraviev.

The key to all doors

The British J&W Sanderson was one of the shareholders of ATEC Holding, which is part of the ATEC Group. BIC discovered that this company is associated with businessman Alexsi Vaganov. According to some media reports, Muraviev inherited the title of “glass king” of Belarus from him. Media reports state that Vaganov was responsible for attracting CPI, the leading Canadian glassware producer, to Yelizovo. This happened six years before the arrival of the ATEC Group at the plant, in 1996.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) financed the arrival of the Canadian manufacturer at Yelizovo. CPI acquired a controlling stake in Steklozavod Oktyabr and committed to constructing a state-of-the-art production line for manufacturing beer bottles and other glassware. However, the Canadian company purchased the plant's share through an intermediary, Lada OMS-Holding, which is associated with Vaganov, rather than directly from the state. [*] [*] It acquired a controlling stake in Steklozavod Oktyabr from the state and added the plant's fixed assets to the authorized capital of the new enterprise. From December 1996 through February 2001, on paper, Vaganov occupied the position of the director of Lada OMS-Holding. The parties may have used this strategy to circumvent EBRD restrictions on direct investment in Belarusian state enterprises.

The partners registered Steklozavod Yelizovo as a joint venture at the end of 1997. KPMG, the international audit and consulting corporation that serviced the transaction, reported that Canadians owned 65% of it, while Lada OMS-Holding and Steklozavod Oktyabr owned 10% and 25%, respectively. Thus, technically, companies related to Vaganov, rather than the state directly, were the partners of the Canadian investor.

The partnership was not successful. In 1998, due to economic and political turmoil, the Canadian investor announced the cancellation of his project in Belarus. Among other reasons for the project's failure, KPMG cited disputes between shareholders. In particular, the Belarusian authorities demanded that the joint venture lease the shops to one of its shareholders, Steklozavod Oktyabr, for a nominal fee. This legal entity was controlled by the company associated with Vaganov.

At that point, Yelizovo's managers took advantage of the company's problems and offered to buy out all CPI's rights in the glassworks at a very low price, a KPMG representative shared. The Canadians faced a complicated situation because the shareholders, who were companies associated with Vaganov, had pre-emptive rights and could block any transaction. They approved the sale of the plant to the ATEC Group for an unknown reason. The transaction was completed in May 2002.

Two months later, in July, the Austrian company gained a co-owner, British Baxworth Trading Limited. [*] [*] Alexsi Vaganov headed this company shortly after it was founded in 2000. From then until at least the fall of 2018, the company's documents show him either as the ultimate beneficiary or as a director. Stateco (Nominees) Limited, an offshore company implicated in the Panama Papers, was the sole owner of Baxworth Trading from 2001 to 2014.

Baxworth Trading owned a controlling stake in Lada OMS-Engineering. Since the company's founding on June 15, 2009, it has owned 58% of the shares, with Vaganov holding 2% since that same day. [*] [*] Vaganov led Lada OMS-Engineering from June 23, 2009, to January 11, 2021. [*]

Moreover, Baxworth Trading owned J&W Sanderson for almost the entire duration mentioned. During the period from November 3, 2004 to July 27, 2007, J&W Sanderson was one of the shareholders of ATEC Holding, and from May 5, 2004 to July 27, 2007, it was a shareholder of ATEC Handelsgesellschaft. [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] [*] We also know that Vaganov was the owner of J&W Sanderson at least until the end of 2002: through J&W Sanderson and Lada OMS-Engineering, he owned another company based in Belarus - UNISON. Vaganov served as a director of J&W Sanderson from May 1, 2015 to February 25, 2020.

Alexander Muraviev, however, disagrees that Vaganov played a significant role in the development of his business. "I remember Vaganov participated in ATEC Holding for two years, but it was only a minor share. He was unable to initiate a meeting or suggest agenda items due to the limitations of his share. So eventually he wanted to sell his share," the businessman said, pointing to his good relationship with Vaganov. According to Muraviev, the latter congratulated him on his release. In fact, Vaganov continued to co-own ATEC for at least five years, not two. First through Baxworth Trading. And then through its British subsidiary, J&W Sanderson.

Alexsi Vaganov was involved in the scandalous UN Oil for Food program for Iraq.

Both the Iraqi press and Vaganov himself confirmed that. According to him, his work in Iraq was supervised by the Belarusian Foreign Ministry. The company Lada, associated with him, was named by the local newspaper al-Mada as one of Saddam Hussein's partners who received cheap oil from Baghdad. Additionally, the list included the Liberal Democratic Party of Belarus. Vaganov was its member.

The UN launched the Oil for Food program in 1995. International sanctions have seriously deteriorated the lives of the people in Iraq. Saddam Hussein's regime was permitted to export oil under the condition that the revenue would be used to purchase food. In the early 2000s, a scandal erupted around the program. It was discovered that food was not reaching Iraqis, and oil sales were only benefiting the Hussein clan.

In its October 2005 report, a UN committee accused almost half of the 4,500 program participants of paying kickbacks to obtain contracts. The scheme involved Iraq selling oil below market value, which was then resold by its partners. The excess profits were then returned to representatives of Hussein's regime in cash. According to UN calculations, the Hussein regime embezzled $1.8 billion in this way. Belarus, which had close contact with the Hussein regime, was among the states charged by the UN.

When ATEC Group began to invest in Yelizovo, Vaganov was a member of the House of Representatives, where he headed the Committee on Monetary Policy and Banking. The press described him as an economic advisor to Uladzimir Kanapliou, first deputy chairman and later chairman of the House. From 1994 to 1996, Kanapliou was the chief assistant to the Belarusian president. He was also considered Aleksandr Lukashenko's closest friend since their student days. They studied at the Mogilev Pedagogical Institute together. Probably, it was his connections that allowed Vaganov to combine deputy duties and business. The law expressly forbade it.

According to the Law on the Status of the Deputy of the House of Representatives, Member of the Council of the Republic of the National Assembly of the Republic of Belarus, a House of Representatives deputy is prohibited from engaging in any paid activities, except for those related to creative work, teaching, and science.

Alexsi Vaganov represented Belarus as a member of official delegations abroad in 2001, 2003, and 2004 at the least:

- In 2001, as part of the delegation headed by Deputy Head of the House of Representatives, Uladzimir Kanapliou that attended the April session of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in Strasbourg.

- In 2003, he participated in the Eighth International Berlin Meeting, together with the Ambassador of Belarus to Germany, Vladimir Skvortsov.

- In 2004, as part of the delegation from Belarus that visited Iran to develop plans for creating an assembly line for passenger cars in the FREE ECONOMIC ZONE Minsk in collaboration with Iran Khodro. Vaganov led the delegation.

“Vaganov became a deputy not because he was popular among the electorate, but because Kanapliou supported him. Furthermore, Vaganov's time in the House of Representatives was not wasted. <...> [He] could influence the wording of draft laws and lobby for his interests. <...> He was consistently ranked among the top twenty or fifty most influential businessmen. <...> Additionally, deputies had limited opportunities to communicate with the government already. But if you are an economic adviser to a person who is one of the top three in the country's political hierarchy, then, of course, any minister will receive you, they will talk to you," Anatol Liabedzka, director of the Centre for European Dialogue, shared with BIC.

Kanapliou retired in 2007. But even after his departure, Vaganov retained his influence and connections with the authorities. In October 2014, he travelled to France on the same day as Deputy Prime Minister Piotr Prokopovich, Deputy Industry Minister Pavel Utyupin, and Interior Minister Igor Shunevich. [*] [*] [*]

Russian partners

Alexander Muraviev names a group of Russian investors as his primary partners. We mentioned several companies as co-owners of ATEC, but only Baxworth Trading and J&W Sanderson were described in detail. But there were others: Permanent Trading, Remolino Trading and Gaflotrade.

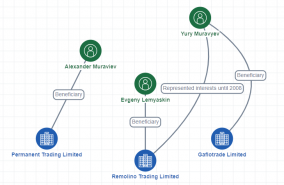

The "Motovelo case" files reveal that Muraviev is the beneficiary of Permanent Trading, while Remolino Trading is owned by Russian Evgeny Lemyaskin. Gaflotrade is owned by another Russian, Yury Muravyev (not related to Alexander Muraviev). [*]

As of 2019, Yury Muravyev owned 93% of the Vorga glassworks in the Smolensk Region, which was part of ATEC Holding. [*] [*] He also used to co-own a mineral water plant in Russia and is still listed as its director. [*] [*] When the Austrians arrived at the Yelizovo Glassworks, Yury Muravyev held the position of Russian official. Specifically, he was responsible for managing the Road Fund in the Nizhny Novgorod Region. [*] [*]

Alexander Muraviev speaks highly of Yury: "As a businessman, Yury is skillfull, he acted independently, and with his ethical and business qualities he made a colossal contribution to the work of the shareholders' meeting, to the work of the shareholders <...> For me it is important that a person should be able to make their own decision. <...> Because if I know that the person in front of me is not a real person, then of course I have to know who the real person is. Yury is real, absolutely real". Yury congratulated him on his release, Alexander Muraviev added.

Two other Russians on the list of partners appearing in numerous other firms along with Yury Muravyev's name are Peter Vaske and the aforementioned Evgeny Lemyaskin. We discovered two transactions between Russian beneficiaries of Yelizovo and other influential individuals in offshore leaks shared with us by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. One involves Anatoly Ternavskiy, Alexandr Lukashenko's biggest oil "moneybag". Vaske's emails to the offshore business service provider MeritServus reveal that they agreed with Ternavskiy on the terms of transferring Steeleron “to him [Ternavsky] from us [Vaske and his client, the beneficiary of Steeleron].” In the same email, Vaske asks the provider to confirm that Evgeny Lemyaskin is no longer Steeleron's beneficiary. Ternavskiy was featured in one of our recent investigations. Peter Vaske was also mentioned there. We know that Vaske is a lawyer and notary public with an office in Moscow.

The second transaction concerned a firm that owned real estate in Belarus, Mainship Realty. It was owned by Yury Muravyev, and later by Vaske and Lemyaskin. Before that, their offshore companies owned it. [*] [*]

Sergei and Nikita Evlakhovs were co-owners in 2014-2015. [*]

Sergei Evlakhov is a former vice president of Transneft. The Russian investigative journal Projekt described him as a confidant of the president of Transneft, Semyon Vainshtok. The latter, in turn, was considered a person close to Vladimir Putin. Nikita Evlakhov is referred to as a venture investor.

Divorcing partners

However, when it came to working with partners, Muraviev did not find all things going smoothly. Vaske was one of the people who represented Remolino Trading. [*] In his testimony in the Motovelo case, he claimed that Remolino Trading had invested about 70 million euros in ATEC Holding. [*] The lawyer insisted that Remolino, through ATEC Holding, invested in and owned Motovelo, the Yelizovo Glassworks, the Homel Glass Factory and Belevrotara. However, these companies, except for the Yelizovo Glassworks, were subsequently transferred to companies controlled by Muraviev without Remolino Trading's consent.

At the same time, Vaske is unaware that ATEC Holding received investment from Permanent Trading, which had Alexander Muraviev as the beneficiary. According to the lawyer, Muraviev used the investment money for personal purchases, including "movable and immovable property in Russia, Austria, and the UAE." [*] The businessman allegedly became wealthy only after Remolino Trading invested in Belarusian enterprises and then lost money. As of 2011, Remolino Trading estimated that Muraviev could have siphoned off about $10 million, Vaske said.

Alexander Muraviev's Russian namesake also seemed to be unhappy with the way he was conducting business. During the pre-trial proceedings, Yury Muravyev testified that the main mistake of the Belarusian businessman was managing all business activities himself. He stated that "there is always a temptation to 'pinch off' from the common purse." [*] He added that in 2008, a dispute arose between Yury, Alexander, and other shareholders. The reason for the dispute was that Alexander Muraviev was running the entire business alone and making decisions without informing the other shareholders.

The reason for the controversy was probably the investment in Motovelo. Yury Muravyev's testimony indicates that he was not involved in the purchase of this asset. Alexander Muraviev decided to invest in it at his sole discretion. But another witness claimed that the deal was negotiated with the Russian, among others. Alexander Muraviev insists that ATEC's decision to buy Motovelo was signed by Yury Muravyev. Either way, as a consequence, Yury Muravyev, who was a director of ATEC Holding from April 15, 2008 to March 14, 2009, left the company. [*] [*]

In response to BIC's questions about the ATEC Group and the Motovelo case, Yury Muravyev said that all the facts relating to his testimony were "100% lies". "The purpose of your e-mail is unclear as Alexander Muraviev has been out of prison for some time and the case has been closed. As an intelligence specialist, I can assert that your email resembles a CIA (perhaps MI-6) template. As they say: It was an honour," said Yury Muravyev in an email to BIC [left unedited for spelling or grammar].

Peter Vaske also spoke at the trial about the conflict between the shareholders of ATEC Holding. He attributed it to Remolino Trading's loss of money and Belarusian assets, which it had invested in through ATEC Holding. In 2010, Vaske appealed to the Belarusian state authorities regarding Muraviev's “abuses” and “fraudulent actions”.

In late 2012, the dispute between the shareholders escalated into a criminal case in Austria. Muraviev was even summoned for questioning.

Other employees also mentioned that incident. Tatsiana Lukavets, the deputy general director of Motovelo, testified that she had learned about the trial in Austria between the shareholders of ATEC Holding from other top managers of the company.

She claimed that the conflict was confirmed by the fact that in late 2011 – early 2012, Irina Tougarinova requested financial statements from Homel Glass Factory, Belevrotara, Yelizovo Glassworks, and Motovelo. During those years, Tougarinova served as a director for ATEC Holding and represented Remolino Trading and Gaflotrade. Vaske stated that she represented Remolino Trading in a dispute among ATEC Holding shareholders in Austria.

According to Vaske, Remolino Trading removed Muraviev from his position as director of ATEC Holding through an Austrian court. Muraviev testified that he ceased to be a director of ATEC Holding in March 2010 when his powers expired. The company's documents show that Muraviev stopped being a director of ATEC Holding on January 11, 2011. [*] [*] The businessman mentioned that 2011 marked the end of his term of office during the Motovelo trial.

But the criminal case was eventually dropped. Motovelo shares were transferred to a third company, ATEC Investment, in 2013. ATEC Investment owned almost 80% of the plant, with RosintechGroup owning nearly 20% by that time. [*]

The director of the latter was Alexander Muraviev's brother, Sergei. Muraviev himself was described as the actual beneficial owner.

ATEC Investment was registered at the address where Alexander Muraviev lived, in the vicinity of Vienna. The businessman did not explain the nature of these proceedings to journalists. He only stated that the criminal case against him in Austria had been closed and that he had reached an amicable settlement with his partners.

A house for the chancellor's friend

Austria was involved in the Muraviev case not only through the settlement of the ATEC shareholder disputes. Belarus requested the assistance of its law enforcement agencies to search Muraviev's house located in the millionaires' estate in the vicinity of Vienna, on behalf of the KGB (The Committee for State Security). [*]

Let's take a closer look at this house. Alexander Muraviev lived in Oberwaltersdorf, a small town located half an hour's drive from Vienna. Before it went into liquidation in 2019, ATEC Investment was registered at the same address. [*] [*] AMETA Holding previously owned this building, but it was sold to Pure Fontana at the end of 2020. Pure Fontana was specifically created for the acquisition of this property, according to the documents. [*] [*] [*] [*] [*]

Vietnamese-Austrian businessman Martin Ho owns Pure Fontana. He is described as a friend of former Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz. [*]Part of the deal was a lease extension. The house was rented by the namesake of the director of the Russian Center for Science and Culture in Vienna at the time of purchase. The U.S. press referred to this person as a recruiting agent of the Russian secret services. Moscow has denied the allegations. The house was sold with him. The terms and conditions stipulated that he would continue to rent the dwelling.

Shatters of empire

Bankruptcy proceedings were initiated shortly before the Motovelo criminal case. This process continued for several years. Homel Glass Factory filed for bankruptcy in 2014, followed by Belevrotara. In 2015, the Yelizovo plant has faced problems as well. It filed for bankruptcy with a debt of almost 600 billion Belarusian rubles (more than $30 million). The company's property and products were sold to Hrodna Glassworks in 2018 after several unsuccessful bids. The enterprise itself was later liquidated.

Alexander Muraviev describes the situation differently: "They didn't go bankrupt, they were robbed. It's different things. Bankruptcy is defined as the financial inability of those involved in the market, who are more or less on an equal footing. Some market players may struggle with managing or selling for various reasons, or they may be making other mistakes."

In 2023, it became known that Muraviev was released. As far as we know, his glass empire had completely disappeared by that point. The Austrian companies owned by ATEC Holding have been closed for several years. ATEC Management was liquidated in 2015, while ATEC Handelsgesellschaft survived till 2017. [*] [*] [*] ATEC Investment, founded in 2006, was dissolved in 2019. ATEC Investment's last owner was AMETA Holding, which was liquidated in 2022. [*] [*] [*]

This investigation is part of the ICIJ and Paper Trail Media's Cyprus Confidential project. More than 270 journalists from different countries worked to uncover the secrets of tax havens. For eight months, they examined 3.6 million confidential documents (1.31 TB of data) made available through leaks from offshore providers using front companies in Cyprus.